In the last couple of posts, we’ve

been exploring the impacts tourism can have on the environment, both on a local

and a global scale. These have not gone unnoticed, and in this blog post the

responses to these damaging environmental impacts - most notably the idea of ‘sustainable

tourism’ - are going to be introduced and explored.

What is Sustainable Tourism?

Sustainable

tourism… ecotourism… responsible tourism…

The United Nations World Tourism Organisation

(UNWTO, 2013: 17) defines sustainable tourism as “tourism that takes full

account of its current and future economic, social and environmental impacts,

addressing the needs of visitors, the industry, the environment and host

communities.”

In other words, sustainable tourism is about applying the

principles of sustainable development more generally to the tourism sector. In this sense, sustainable tourism isn't exactly a special form of tourism for a niche market, but instead a goal to make all types of tourism in all destinations more sustainable (UNEP, 2005). Given the dramatically increasing number of

tourist arrivals in the late 20th century, sustainable tourism isn’t understood as an alternative to mass tourism; well-managed mass tourism can and should be as sustainable as smaller-scale tourism (UNEP, 2005).

I'm not sure the elephants' idea of 'getting close to nature' was what the ecotourists had in mind... (Source)

What does Sustainable Tourism Involve?

Regarding the environment, sustainable

tourism aims to “make optimal use of environmental resources that

constitute a key element in tourism development, maintaining essential

ecological processes and helping to conserve natural resources and

biodiversity” (UNWTO, 2013: 17).

Right, well that’s all well and

good, but in reality achieving this goal is pretty difficult and complex.

Let’s go back to the first definition of

sustainable tourism – “addressing the needs of visitors, the industry, the

environment and host communities” (UNWTO, 2013: 17). As this quote exemplifies, many different stakeholders engage with the tourism sector, or influenced by it. All these groups have different interests and

levels of influence on the industry. Yet a critical requirement in sustainable tourism's success is for stakeholders to collaborate effectively in management

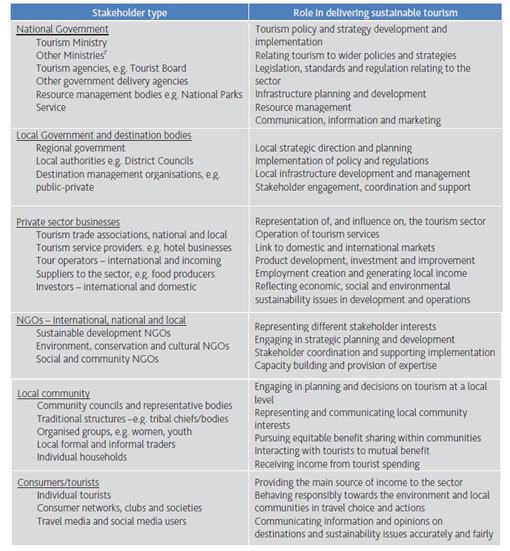

of the sector, making their roles and relationships in the implementation of sustainable tourism very important. This requires organised coordination and partnerships, both at the local and national destination levels (UNWTO, 2013) - often easier said than done. Figure 1 gives an

overview of just a small number of the stakeholders involved in the industry and what their

roles could be in achieving sustainable tourism.

Figure 1. Different stakeholders in the tourist industry and their suggested roles in delivering sustainable tourism. Adapted from UNWTO, 2013.

Alright – so we’ve gone over the

need for stakeholder coordination in achieving sustainable tourism – so what

actually needs to be done? What actions can go about making “optimal use of environmental

resources” and “maintaining essential ecological processes”? (UNWTO, 2013).

Well, there isn’t really a straightforward answer to this…

The UN World Tourism Organisation

identifies measures like planning controls, financial incentives and certification as ways to promote sustainable tourism in a destination

(UNWTO, 2013). But do these actually work? Buckley (2012) argues that so far, attempts made by the private sector to achieve sustainability, such as self-regulation and ecocertification have been pretty much ineffectual. This is for a number of reasons. Private companies often opt for environmental

self-regulation in order to avoid stricter external government regulation (Núñez, 2007). In this way, they can carry on with environmentally unsustainable practices under the guise of sustainable tourism (Buckley, 2012). Furthermore, Mair and Jago (2010) argue few tourists themselves choose between services specifically

based on their sustainability; instead they generally expect good environmental practice to be incorporated into services as routine. As an avid traveller I’d

say I have to agree – I can't say I've ever chosen a particular airline or hotel purely

based on its environmental performance.

Instead, it has been suggested that

environmental policies, management measures and technologies have greater

potential to reduce the environmental impacts of tourism

(Buckley, 2009; UNEP, 2011). For example, advances in energy efficiency can help reduce waste generation and resource consumption locally (Buckley, 2012). Furthermore, although most environmental damage linked to tourism is caused by private companies and tourists, governments should take a leading role in achieving sustainable tourism (UNEP,2005; Buckley, 2012). Strong leadership is needed because the tourism sector is really fragmented and coordination

between stakeholders for an effective sustainable tourism strategy. Governments have the necessary authority to implement strict environmental regulation and economic incentives on private businesses, which Buckley (2012)

argues is the main driver for improvement. For example, improved sustainability in

hotels can be driven by measures such as local government regulation for

planning, external impact assessment and pollution control (Buckley, 2012). Similarly, NGOS

have an important role in coordination and getting the voices of less powerful stakeholders heard – such

as the local community, smaller businesses and tour operators (UNWTO, 2013).

The Future...

Lastly, the need for quantitative and widely applicable sustainability indicators for the tourist sector has long been recognised. This article in the

Guardian from a couple of years ago argues it is the role of local

governments and authorities to collect this globally comparable quantitative

information on the environmental impacts of tourism in particular destinations.

It is this lack of precise information on destinations which hinder the

development of direct targets.

Regardless of who is responsible for collecting the data, coming up with the indicators is a difficult task – how would you define a sustainability indicator? What would you include in it? Nevertheless, establishing quantitative and comparable environmental performance measures should be a key priority for sustainable tourism research (Buckley, 2012).