Tropical coral reefs cover less than 1% of the ocean, yet rival only rainforests as the most diverse ecosystems on Earth, providing vital services such as home

and nursery to a quarter of all marine

fish species. They are of utmost importance to humans and our economy, with 500 million people dependent on them for livelihoods. Healthy coral reefs are especially important for local tourism,

through providing appeal for diving tours and fishing trips; furthermore,

businesses based near reef systems such as hotels provide millions of jobs and

income globally (Figure 1). Yet the latest global coral reef assessment states an estimated 19% of coral reefs are now dead and lost, and the tourism

industry is far from guilt-free.

Figure 1. The breakdown of component values that contribute to the global

annual economic value of coral ecosystems. Source.

Over these last three decades

(e.g. 1990s,

2000s,

and 2010s much of the research on tourism’s impact on coral reefs has centred on recreational

activities, particularly snorkelling and scuba diving.

A survey of the bay’s benthic

community in 2013 compared sites in a snorkeller-intense zone with those at a proximate control zone featuring 13 times lower tourist numbers (Figure 2). The results show lower coral cover across all coral

morphologies in the high-tourism zone, (although this effect was only

significant for plating coral cover). Furthermore, tourism-intense sites featured significantly increased dead coral cover (a 50.5% increase from control to tourism sites; p < 0.05), and a greater abundance and number of taxa of

benthic algae, although this was not significant.

The study focuses on the

increasing number of snorkellers as the causative variable for reductions in coral cover in the high-tourism zones. I agree that the presence of snorkellers and SCUBA-based reef tourism can drive coral reef degradation. Indeed, similar

results are found in a number of different studies throughout the years. You can imagine why – to describe just a couple of mechanisms: direct, physical contact of snorkellers with corals (trampling, touching) can easily degrade coral skeleton and tissue, and snorkellers can

cause localised water column sediment re-suspension, reducing recruitment and survival of corals through choking them.

*

However, Gil et al.’s (2015) use

of variables such as ‘no. of tourists in water’ and ‘number of snorkellers’ effectively

lumps together all activities associated with snorkelling – from the individual snorkellers to the dive boats and anchors and their associated impacts. Because

of this, I was sceptical as to whether the reductions in coral cover in the

high-tourism zone (Figure 2) were really down to individual snorkellers, or

whether there could be other tourism-related activities associated with the

increasing numbers of snorkellers driving that difference, which was

encapsulated within their metric of ‘number of snorkellers’, but not quite

specified.

A bit of digging later, I found an

excellent (albeit slightly dated!) study quantifying the degree to which separate tourism activities individually impact

on coral reefs. Two of these impacts - dropping anchors and their chains on

reefs and physical diver contact – both could have been encapsulated in Gil et al.,’s (2015) variables ‘no. of tourists in water’ and ‘number of snorkellers’ and thus driven

the reductions in coral in the high tourism zone (as an increasing number of

snorkellers could also entail an increasing number of dive boats dropping

anchor). The results of this study took me by surprise; given the volume of

research on the impacts of snorkelling and SCUBA diving on coral reefs, I

assumed the greatest impact on coral cover would be from physical diver

contact. However, anchors and their chains (from dive boats) had a whopping

mean coral cover damage of 7.11% in contrast to a very moderate diver contact mean of 0.67%.

Dropped anchors can break live portions of a coral colony into fragments,

gouging out large chunks of coral skeleton and tissue – which often die and

turn into rubble clouds, choking the surrounding corals. In contrast, the model

results indicate that SCUBA divers and snorkelers tend to damage coral reefs on

a smaller, individual scale. This would suggest that perhaps ‘number of

snorkelers’ is a slightly simplistic metric when advising management, as it

largely overlooks the difference in impact between separate activities

associated with rising snorkeler numbers. A manager reading Gil et al.’s (2015)

paper may focus on

educating snorkelers on coral damage – when in fact they should be focusing on

initiatives such as designated mooring lanes for dive boats to reduce coral

damage!

Furthermore, the focus on snorkelling

and SCUBA diving in the wider field of tourism-related coral disturbance

research fails to appreciate the more indirect impacts of coastal tourism

development on reefs. Such development increases land-based runoff events that drive nutrient enrichment (a global problem which can occur for example where hotel sewage is allowed to enter the coastal

system) and sedimentation, promoting benthic algal domination over corals.

Indeed, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administrations (NOAA)’s ranking of major threats to coral reefs ecosystems by region shows that coastal development and runoff poses a high priority threat in 10/14

regions of the world, as opposed to only 1/14 for tourism and recreation

(Figure 3).

Figure 3. Ranking of major threats to coral reef ecosystems by

region. Source.

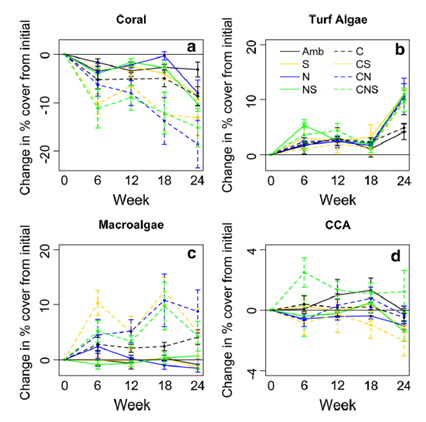

A recent experimental study based on coral reefs in the Gulf of Panama showed that coral loss and algal

growth induced by overfishing was magnified and accelerated when sediment

addition or nutrient enrichment was combined with overfishing (Figure 4). It

has been argued that overfishing is the fundamental factor driving community

shifts to algal-dominated tropical coral reefs.

This indicates that coastal tourism development can play a major role in coral

reef degradation through exacerbating the pressures already being placed on

coral reefs, such as overfishing.

Figure 4. Change in benthic composition over the experimental period. Changes in percent cover from initial values displayed in separate panels for different community members. Lines, styles and colours indicate the effects of different combinations of stressors:

overfishing = dashed lines; sediment addition = yellow lines; nutrient enrichment = blue lines; both nutrient enrichment and sediment addition =

green lines. Source.

An overall point of this post is that the localised

impacts of tourism on coral reefs often co-occur, and damage cannot be

attributed to divers alone. A final take-home point is that these local impacts

are always experienced in the presence of global anthropogenic stressors, such

as increased sea surface temperatures and ocean acidification,

and regional-scale natural disturbances to coral reefs such as the El

Nino-Southern Oscillation or hurricanes, which could also see shifts in their regimes in the near future due to climate change.

In fact, this year’s El Nino event may even outdo the peak event of 1997-98,

meaning that coral die-off in 2016 could be particularly severe as the

bleaching event causes them to lose their algal coating.

The tourism industry itself is increasingly contributing to these global

pressures, for example through releases of greenhouse gases associated with

increasing air travel (see my previous post!).

This is important because the background effects of climate change are expected

to generally reduce ecosystem resilience, increasing the impact of tourism’s local

stressors.

This online photo gallery dramatically illustrates some of the

horrific effects of human impacts on coral reefs discussed in this blog post.

*For more info on the direct impacts of snorkelers and

SCUBA divers on coral reefs – check out this blog!

There are also ways in which tourism can be beneficial for coral reefs. In the Wakatobi Marine National Park, Indonesia, there are two ecotourism operators, both of which provide direct economic incentives to local fishing villages in return for the designation of no-take areas adjacent to their tourism resorts, where no fishing or other extractive/ damaging activities are allowed - including anchoring of boats. The tourism operators want pristine coral reefs to attract customers, and so it is in their best interests to protect the reefs, which they are able to do through their economic power. There are obvious issues here with private organisations assuming the role of park authorities, but overall the present of these tourism operators is of direct ecological benefit to the coral reefs. So, do you think that if tourism operators don't use damaging practices (such as anchoring their boats on the reef), and educate their customers, they could actually be beneficial to the coral reefs, through their own interests in the health of the reefs?

ReplyDeleteHi Lucy! What a brilliant and positive example! I agree that marine protected areas are key to preserving coral reefs in tourism-intense coastal sites, as illustrated through your example. I think that tourism operators can, and should, make it their duty to reduce damaging practices as described in my post, and education is definitely important. Those tourists aware of the damage they can yield on corals are much less likely to break/trample on them etc. I agree that it is in the best interests of operators themselves to protect reefs, and it will benefit them in the long-run if they invest in protection through no-take MPAs and education.

ReplyDelete